These past years, my vintage collection has expanded mostly thanks to generous — sometimes very generous — donors. These last additions, instead, came from a ‘rescue mission.’ It’s been a while since I did my last, and I had missed the fun. Thanks to a valuable tip from my brother-in-law, I learnt that a local design studio was getting rid of a few vintage Macs and assorted accessories and peripherals, and they were basically telling people on social media to come and get them.

If you’re a regular reader of this site, you’ll probably understand how I felt. I couldn’t pass up such an opportunity. From the photos the design studio put online, I knew I couldn’t take much with me (there were bulky printers, several beige desktop Macintosh G3 machines, a couple of older Power Macintosh 7300, an 8600, and a few graphite Power Mac G4s, plus three boxes of miscellaneous things covered by an intricate web of Apple ADB mice and SCSI cables), so I resolved to look for useful peripherals for my data retrieval service, and to rescue at least one of those Macs. I wish I could have taken more stuff away with me, but unfortunately I just don’t have the space.

As much as I love older machines, my interest was piqued by those graphite Power Macs. When I got there, I noticed that one of them had already gone. The remaining two were very similar, but one had an internal ZIP drive, the other did not. I have several ZIP disks, plus my PowerBook 5300 and PowerBook 1400 both have ZIP modules, then I have two other external ZIP drives — one SCSI, one USB — so ZIP disks are often a quick way to pass files among my vintage Macs. So, this Power Mac G4 with an internal ZIP drive was already drawing my attention. Still, I wanted to check the specifications of both Macs to see which was the better machine. Thankfully, Apple has this nice habit of indicating a Mac’s base configuration either on a label or by printing it on the computer itself. I wasn’t in a comfortable position, crouched behind the Power Macs, trying to read the tiny labels, but I managed to catch a 400 MHz on the label of the ZIP-less Power Mac, and a 500 MHz on the ZIP-equipped one, so I chose the latter.

Then my attention turned to the various accessories scattered nearby. There were a couple of Apple Extended Keyboard II keyboards, so of course I picked up one:

I already have one, but it has the older QZERTY Italian layout, which I find particularly difficult to adjust to. This has the equally older Spanish layout, but it’s QWERTY, and shares more keys in the same position as the US/UK/ITA Pro layout I’m more accustomed with. (I still haven’t cleaned the keyboard thoroughly, but it’s not bad after a first pass, and believe me, you didn’t want to see a photo of its original condition!)

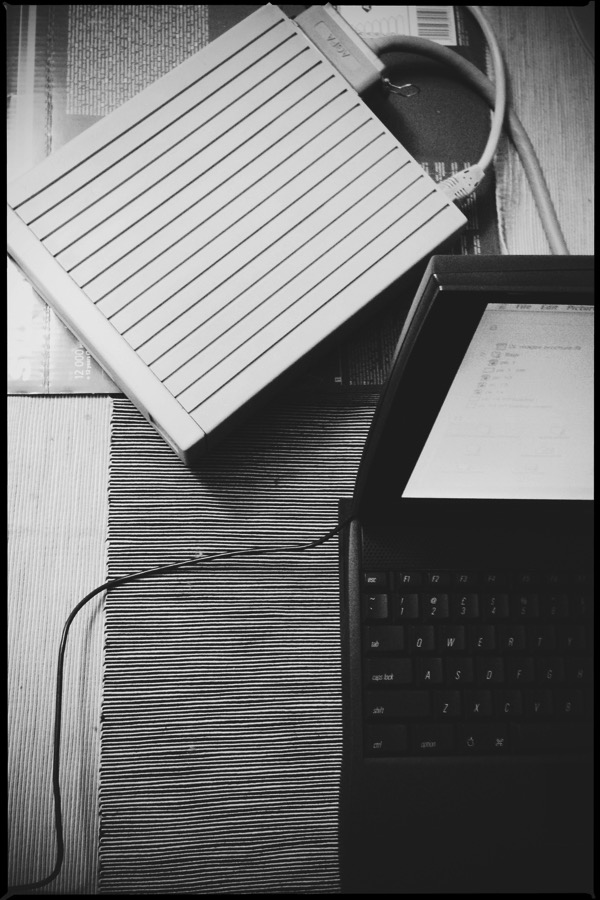

Next up, another very interesting peripheral:

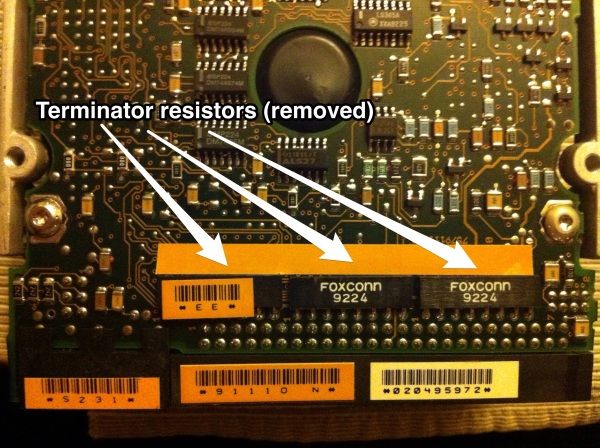

It’s not a bulky floppy drive, but a 3.5″ Fujitsu 230 MB SCSI Magneto-optical drive. There was a SCSI cable in good condition attached to it, plus that SCSI passthrough terminator you see in the photo. I took the whole package.

Last month I thought to myself, It’s a pity I don’t have a USB floppy drive, it could be useful for quick data retrieval without having to take out a floppy-equipped Mac every time I need to read one. Guess what I found among the tangle of SCSI cables:

It is the typical ‘Made in China’ unbranded affair, but I briefly tested it, and it works. So no complaints here.

I didn’t want to overstay my welcome. There were other things I could have picked up — keyboards, mice, cables — and other things that would have needed further inspection and more time. Then there was at least one thing I regret not taking: a 17-inch CRT Apple Studio Display, but I really really have no space for such a cumbersome item.

If you’ve never seen one in person, you can’t imagine how imposing this thing is. To give you an idea, it’s bigger than an iMac G3, and is closer to an eMac in size and bulk. It would have made a nice companion for the Power Mac G4, but I guess I’ll look for the flat-panel 17-inch Studio Display, certainly more manageable.

Just as I was leaving, beneath a pile of other non-Mac equipment, there was this nice-looking cassette deck, a TEAC V-210C, manufactured around 1988:

I still have hundreds of tapes, and my Sony stereo cassette deck broke down a couple of years ago, leaving an old Aiwa walkman as my sole means to listen to cassette tapes. I asked the guys of the design studio whether it worked or not and they told me something along the lines of Who knows, but take it home and find out yourself, heh heh. So I did. And it works!

More about that Power Mac G4

Above I said that I chose what appeared to be the better Power Mac by having a cursory glance at the label with the base configuration attached on the back of the machine. Once home, I examined it more carefully, and I was pleasantly surprised by a little detail I’d missed. The label actually says: 500 MHz / MP / 1M CACHE / DVD-V / 256MB SDRAM / HD 40G / 56K MDM. That “MP” stands for Multi Processor, making this a Dual 500 MHz Power Mac G4!

Another bonus: it actually came with 640 MB of RAM, and equipped with a SCSI card as well, which never hurts. The Mac was apparently last used in December 2008 and contained three user accounts which were basically empty. I had to use the Mac OS X Tiger DVD to boot the Mac and enable the root account, which I used to inspect the user accounts and then delete them. Among the software goodies: a full installation of Adobe CS3, plus FreeHand, StuffIt 12, and NeoOffice.

I was happy to find four 512 MB RAM sticks in my stash, which happened to be the exact type supported by this Power Mac, and voilà — I have brought it to the maximum RAM supported: 2 GB.

The Mac came indeed with a 40 GB IBM Deskstar hard drive, which I discovered to be a 7200rpm drive. A quick check with Disk Utility didn’t find any problems with it. It’s rather fast, although a bit on the noisy side. The Mac also has a Combo optical drive: it reads CDs and DVDs, and writes CD-Rs and CD-RWs. My initial tests show that it works reliably when it comes to reading discs, not so much when writing them. But what I’m most bummed about is the ZIP drive, which doesn’t seem to work. System Profiler sees it, the unit appears to work when inserting disks, but nothing happens afterwards, and disks (even formatted, known-to-work disks) aren’t mounted on the desktop or detected by Disk Utility.

I thought it was a matter of drivers, but Mac OS X Tiger doesn’t need them to read ZIP disks from an internal drive. I thought it was a matter of jumper configuration on the back of the unit, but I’ve read that its current jumper-less configuration is the right one. I’ve seen units like this go for €25-30 on eBay; I also have an excellent DVD-RW/CD-RW drive salvaged from another computer — I might replace both in the future and have a fully-working Power Mac G4. Still, I really can’t complain. The Mac works very well, and the combination of dual G4 processors, 2 GB of RAM, and a 7200rpm drive makes for a surprisingly snappy machine overall. TenFourFox is quite responsive, possibly even more than under Mac OS X Leopard on faster machines. This is the Gigabit Ethernet Power Mac G4, so network transfers are very fast as well. This Mac has space for another two internal hard drives, so I’m thinking it’s a good candidate to act as a home server of sorts. I can’t wait to put it through its paces.

Everything else works

The Apple Extended Keyboard II only has one unresponsive key, but I’m reserving judgment until I have a chance to clean it thoroughly (it’s very dirty under the keys). The USB floppy drive works. The Fujitsu Magneto-optical drive works too: I was donated a 230 MB magneto-optical disk and last night I was finally able to access it on the PowerBook 1400:

And, as I already mentioned above, that TEAC cassette deck works as well. I’m very happy to be able to listen to tapes (and old mixtapes) again on my hi-fi stereo.

In conclusion, I wish I could have rescued more stuff (oh, that Studio Display!) but I’m quite satisfied with what I ended up selecting. The Dual 500 MHz Power Mac G4 is the most powerful machine of all those that were up for the taking, so… mission accomplished nonetheless!